The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the widespread adoption of telehealth. Many hoped that as a consequence practices would be able to leverage the technology to address existing health inequities in an innovative way. With practices offering telehealth to a broader section of patients, those who typically struggled with healthcare access might now find it easier to get the care they needed.

Increasing the availability of telehealth does not, in and of itself, eliminate barriers such as digital literacy and the availability of technology, but that didn’t keep everyone from hoping. In time, they thought, such challenges could be overcome through advocacy, training, and innovation.

Now, new research from athenahealth shows that although telehealth has delivered on this promise in some ways, the benefits are not being felt equally by all groups.

A recent analysis of trends in telehealth usage among athenaOne network patients between 2019 and 2022 found that while virtual services increased during that time, improving access to care for many, some inequities in telehealth usage persisted.

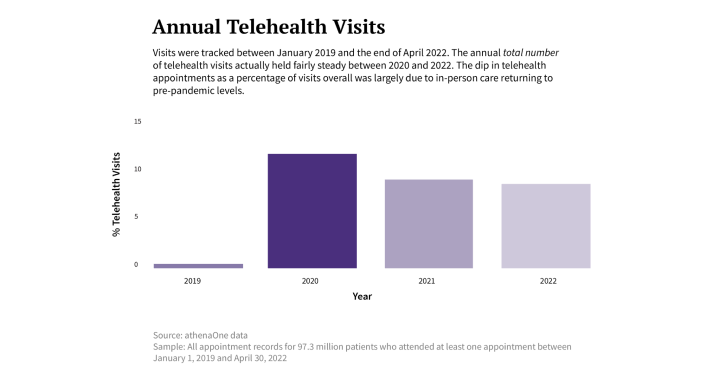

COVID-19, the research revealed, drove the initial rise in telehealth adoption across the network, but telehealth usage has remained higher even as pandemic-related restrictions expire. While virtual care accounted for just 0.4 percent of all network visits in 2019, that figure jumped to 12.9 percent in 2020 before dropping slightly to 8.9 percent in 2022.

This increase in telehealth utilization, however, was not consistent across certain populations historically associated with health inequities. Lower-income and rural patients, for example, used telehealth less often than those who were more affluent or living in metropolitan areas; and while Black and Hispanic patients were more likely to use telehealth than their white counterparts, they were less likely to do so with a dedicated provider within a single practice.

“I think what we’ve seen is that telehealth wasn’t the panacea some believed it would be,” says Allyson Livingstone, athenahealth director of diversity and inclusion. Telehealth can be an equalizer for healthcare access, she notes, “but facilities first have to offer it as a service, and then they need to commit to patient outreach and support.”

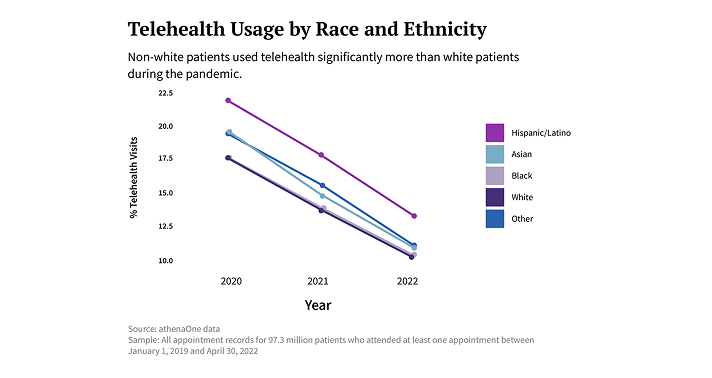

Use of telehealth varied by race and ethnicity

Perhaps the most interesting finding from the analysis was that Black and Hispanic patients used telehealth at high rates, but in a very different way than white patients.

The graph below illustrates that Hispanic patients had the highest percentage of appointments occur virtually of any racial group in the patient population, while Black patients had similar percentages of virtual visits as white patients. After adjusting for other patient and appointment characteristics (like age, sex, type of appointment, etc.), the analysis found that racial differences were even more pronounced. Hispanic patients were 51 percent more likely than white patients to have an appointment occur virtually rather than in person between 2020 and early 2022, while Black patients had 20 percent higher odds of attending an appointment virtually than their white counterparts.

When the researchers looked at only patients with a single dedicated provider within a practice — for example, a patient who always sees the same primary care physician at a clinic or has an ongoing relationship with a single endocrinologist — and predicted whether the patient attended even a single telehealth appointment with that provider, the racial trends were reversed. Hispanic patients with a dedicated provider were 8 percent less likely to use any telehealth compared to white patients with a single consistent provider. And a similar drop was seen among Black patients in this category, who were 12 percent less likely to adopt telehealth than comparable white patients. These findings show that, while Hispanic and Black patients clearly have access to telehealth services, they may be less likely or able to adopt it with their dedicated providers.

The data, Livingstone explains, may indicate that non-white patients relied on telehealth for the same reasons people without primary care providers often turn to emergency rooms and urgent care facilities. Other studies have clearly documented how race and ethnicity factor into access to consistent care. “It could be that in many cases, a telehealth appointment with any provider was their only option,” she says.

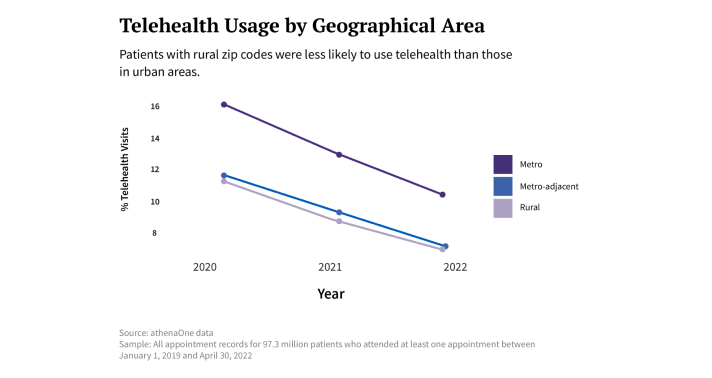

Poorer patients and those in rural areas used telehealth less

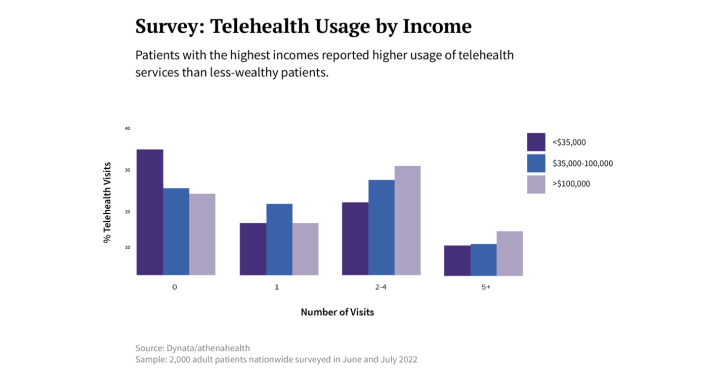

That patients with lower incomes or living in rural areas would use telehealth less than wealthier or urban patients during the pandemic also ran against many people’s expectations. Between 2020 and 2022, the data show, patients with urban zip codes relied on telehealth appointments anywhere from 30 to 50 percent more often than their rurally located counterparts, while patients making more than $100,000 per year were significantly more likely to have at least one telehealth appointment than those with annual incomes under $35,000.

Telehealth improved care for some rural patients, and it improved care for some poor patients, Livingstone says. “But most of all, what it did was make care more convenient for city dwellers and the financially secure.”

Not helping the matter, she adds, was the fact that rural facilities offered telehealth services far less frequently than urban ones did. And another likely reason for the discrepancy: the “digital divide” between rich and poor.

At facilities where at least 75 percent of patients live in rural areas, only around 4 percent offered telehealth between 2020 and 2022. By contrast, at facilities where fewer than 25 percent of patients live in rural areas, 94 percent included telehealth as a service.

Federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) were very likely to adopt telehealth services, but their patients were still more likely to receive in-person care compared to patients at other types of practices. Similarly, across all practice types, Medicaid patients were less likely than Medicare or commercially-covered patients to use telehealth during the study period.

“It’s impossible to access telehealth if your practice doesn’t adopt telehealth tools,” Livingstone notes. “And even when a practice does offer telehealth, how does that help a patient without a smartphone or computer, or if they live in an area that doesn’t have broadband?”

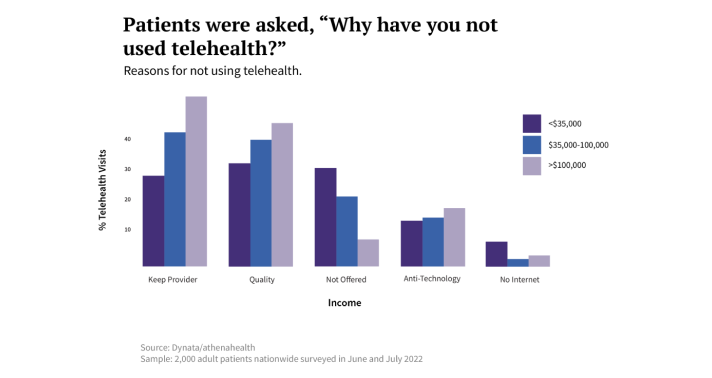

Patient survey sheds light on research results

Overall, the telehealth data tell a story that aligns with the findings from a survey of 2,000 adults commissioned by athenahealth in the summer of 2022. Among those who took part in the poll, 66 percent reported they’d had at least one telehealth appointment since the beginning of 2020.

The survey revealed that when poorer patients didn’t use telehealth, they usually reported it was either because the service wasn’t offered or because they lacked the technology they needed. Many higher-income patients who didn’t use telehealth, on the other hand, said their non-utilization was a matter of choice: They preferred to see their provider in person or they worried that a telehealth appointment might be of lesser quality.

Wealthier patients were also more likely to say they didn’t use telehealth because they wanted to maintain a consistent provider — presumably because booking a telehealth appointment would have required them to see someone new. (This echoes the findings for Black and Hispanic patients, whose telehealth appointments were often with a different provider.) Nevertheless, survey respondents making more than $100,000 annually reported higher use of telehealth than lower-income patients did.

Finally, among those patients who did use telehealth, the wealthier were more likely than poorer patients to say that if a telehealth consultation hadn’t been available, they would have booked an in-person appointment instead. Livingstone’s interpretation: “Telehealth may be a more important form of access for lower-income individuals.”

Taken together, the network data and patient survey highlight the rising importance of telehealth for access to healthcare for marginalized groups, even as they also expose inequities that aren’t automatically eliminated by increased telehealth. But understanding how telehealth is falling short on access can help healthcare organizations be more thoughtful in their deployment and support of the technology — and provide a roadmap for future virtual efforts.

“I think the message is clear,” Livingstone says.

Telehealth can do a lot of good, but we shouldn’t see it as a solution on its own.